Source: CoStar News

By: Lou Hirsh

February 11, 2020

A new list of the federal government’s surplus properties targeted for disposal includes what brokers say is real estate that’s expected to be in high demand by developers of offices and housing in some posh West Coast locales where land is tight.

What’s more, the decades-old properties — most of them underused offices — could be revamped for new uses, ranging from distribution centers to high-end apartments, retail and other mixed-use combinations that could bring new life to the areas, brokers and analysts say.

On the list, which contains 12 underutilized properties nationwide that could bring in more than $750 million, is real estate in areas where development and business have been growing from Seattle to Silicon Valley. It includes an entire city block just three miles from Facebook’s headquarters in Menlo Park, California, that could soon be for sale.

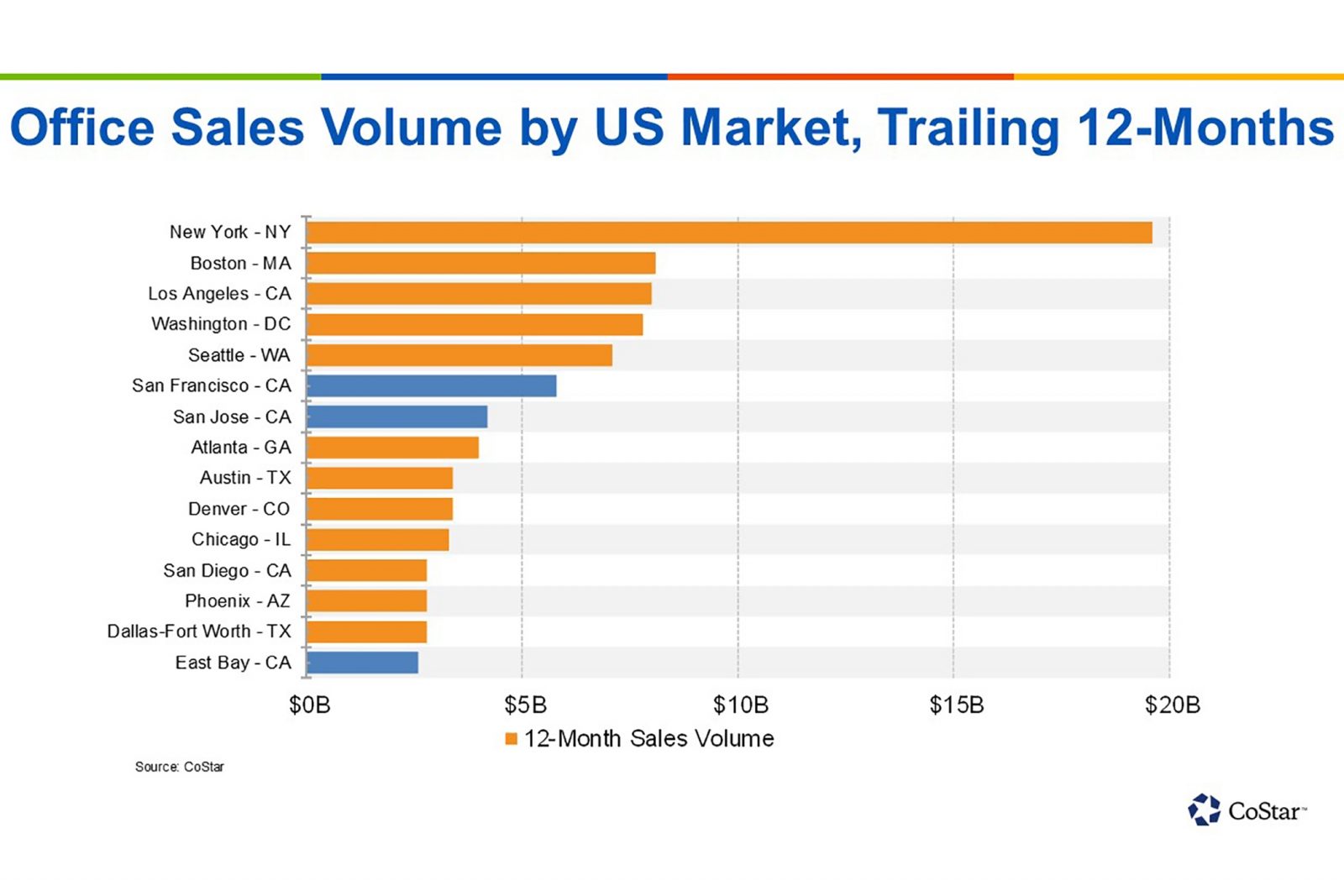

“The Menlo Park property is located in one of the country’s strongest markets for tenant demand,” said Jesse Gundersheim, CoStar Group’s director of market analytics in the San Francisco Bay Area. “Sales activity in Silicon Valley and San Francisco is robust, and cap rates remain at historic lows which is indicative of strong investment interest.”

The surplus property list put forward last month by a federal advisory panel stems from a bipartisan 2016 law requiring the Office of Management and Budget and General Services Administration to identify opportunities for the federal government to reduce its inventory of nonmilitary properties. The list is just the first round of potential sell-offs, with more rounds of recommendations expected in coming months, as the government looks to consolidate locations, maximize property values and revenue and trim down a real estate portfolio that includes roughly 77,000 underutilized properties.

Some that aren’t in their city’s downtown or prime office district could face the bulldozer, as developers put the land underneath them to more suitable uses demanded by the market, such as apartments and single-family homes — provided their projects get the blessing of local governments.

Take for instance the property at 1352 Lighthouse Ave. in coastal Pacific Grove, on the northern tip of central California’s Monterey Peninsula. The property, that CoStar data says was built in 1952 and spans 11,220 square feet on 4.4 acres, is a Department of Commerce fisheries science center.

Located just 5 miles north of the famed Pebble Beach Golf Course overlooking the Pacific Ocean, that federal facility sits in a city where the median home value is $902,528 and the median monthly apartment rent is $3,300, according to data firm Zillow.

“That location could be very sought-after for high-end housing,” said Cale Miller, senior vice president in the San Francisco office of commercial brokerage Hughes Marino, noting the neighborhood currently hosting the fisheries center is generally not known for offices or other heavy commercial uses.

The same generally goes for the 1 million-square-foot Chet Holifield Federal Building, built in 1971 at 24000 Avila Rd., about 8 miles from the Pacific Ocean in coastal Laguna Niguel. That city, in Southern California’s Orange County, has a median home value of $844,539 and median rent of $3,300, both well above regional averages.

Miller said housing or other mixed-use elements serving that neighborhood — rather than offices — would probably see the most practical demand going forward.

Coveted Silicon Valley

At the other end of the spectrum, brokers are expecting the listed property in Silicon Valley’s Menlo Park to see the greatest future demand on the office side. Washington, D.C., attorney David Winstead, who serves on the federal building advisory board, recently told CoStar News that the city block surrounding the Menlo Park Complex at 345 Middlefield Road “could be worth hundreds of millions of dollars.”

With multiple major tech firms expanding their office footprints in the supply-constrained region, the location is a major draw. The Menlo Park federal complex, housing the operations of the U.S. Geological Survey among other tenants and spanning just more than 140,000 square feet, is 3 miles south of Facebook’s global headquarters and even closer to local office strongholds of companies such as Apple and Hewlett Packard.

“Menlo Park has been ground zero for tech expansion,” said Eric Luhrs, regional president in the San Jose office of brokerage Kidder Mathews. “That’s still a very strong market, and that’s a great location as well.”

Luhrs said he’s expecting the Menlo Park location to garner serious interest from multiple developers and future tenants, including the venture and financial firms that have thrived in Silicon Valley. It could also attract smaller nontechnology firms that have found it tough to find new space as the major tech giants, including Facebook and Google, have expanded throughout the region.

Gundersheim noted that, based on its size, more than a million square feet on a 100-acre lot, the Laguna Nigel property could prove more valuable on a pure sales-price basis than the Menlo Park site. However, the Menlo location could represent a rare investment opportunity slightly east of that city’s most active section, the downtown area where most developers are now focused on revitalization.

In Menlo and other office locations, Luhrs said changeovers to commercial uses will depend on how the government chooses to transition out of them — for instance, whether the GSA sells buildings and immediately clears out the agencies that occupy them or chooses to stay in them for a period under leaseback arrangements with the buyer.

In the Seattle area, where older federal buildings on the list are not located in what are currently deemed the hot office markets, other types of nonresidential buyers and tenants could still find strategic uses for the properties.

That includes the property currently known as the Federal Archives and Records Center, operated by the National Archives and Records Administration at 6125 Sand Point Way NE. The warehouse and office building was completed in 1945, spanning 184,251 square feet on 10 acres.

Owen Rice, executive vice president in Hughes Marino’s Seattle office, noted the area that grew up around that Seattle facility over the decades is primarily a residential neighborhood, known as Hawthorne Hills.

“That area has not really been a big hub for commercial offices in terms of demand,” Rice said. “It’s also a very constrained market in terms of supply.”

Alternate Seattle Scenarios

He said possible future nonresidential users of that government complex could include those in the fast-expanding healthcare industry. For instance, Seattle Children’s Hospital has existing operations next door to the Sand Point Way property and is known locally to be scouting sites for future expansion.

Rice said another vintage property on the federal list in Washington state, a government complex at 400 15th St. SW in Auburn, is located in an area just north of Tacoma that has become a popular regional hub for mostly small to mid-size industrial developers and tenants.

He said the 119,000-square-foot property, built in 1950 and last renovated in 2006, has good access to area ports and freeways but is in an area of the Kent Valley that has so far not become a hotbed for office expansion by major tech giants such as Amazon. The e-commerce giant has been expanding its corporate hometown operations primarily in and near downtown Seattle.

It could take several office tenants to fill up the space at the Auburn facility, based on the size of companies that are currently predominant in that area, leaving the possibility for industrial and other uses of the property if it is sold off by the government.

“It really depends on what the zoning would allow and what the developer would want to do with it,” Rice said. “It’s hard to imagine that someone would want to tear down a building that was just renovated in 2006, but that’s a possibility.”

Miller said other factors to watch include how fast the properties get sold off by the government and whether officials decide to sell them as one or two large portfolios, or instead choose to shed some individually in one-off deals.

In several locations, the government could get more for the properties by selling them separately, but finalizing several separate deals could also take longer to dispose of the assets and garner the revenue that the government is seeking.

“They’re going to be incentivized to sell these in a relatively short time frame, if they’re looking to capitalize while the market is still at its current peak,” Miller said.

Because some of the federal properties are older and not in neighborhoods deemed the hottest for offices, brokers said their future owners will probably require substantial financial resources to weather long transition periods in which the properties are being approved for significant renovations or repurposing.

That’s a potentially time-consuming prospect in states such as California, where projects must clear numerous environmental and other hurdles, especially in coastal locations.

“It’s going to take patient money, from experienced developers who are able to afford the carrying costs for a project that might take five years to approve,” Miller said.

These are the Western U.S. properties on the national list of locations recently targeted for potential sell-off by the GSA:

Sacramento Job Corps Center, excess land sale only, 3100 Meadowview Road, Sacramento, California, Department of Labor.

Southwest Fisheries Science Center, 1352 Lighthouse Ave., Pacific Grove, California, Department of Commerce.

Veterans Affairs Denver Medical Center, partial sale, 1055 Clermont St., Denver

Auburn Complex, 400 15th St. SW, Auburn, Washington, GSA.

Menlo Park Complex, 345 Middlefield Road, Menlo Park, California, GSA.

Chet Holifield Federal Building, 24000 Avila Road, Laguna Niguel, California, GSA.

WestEd Office Building, 4665 Lampson Ave., Los Alamitos, California, Department of Education.

Federal Archives and Records Center, 6125 Sand Point Way NE, Seattle, National Archives and Records Administration.

Link to article: Government Surplus Properties